This post originally appeared on the Carbon Talks blog.

British Columbia’s Carbon Tax has been getting a lot of media attention in the last few days, and rightly so. While it is not without its skeptics, much of the opposition seems to grow out of a misunderstanding of how the tax works. This stems from an unfortunate reality when it comes to taxes: the public always wants less. What may be an easy talking point for a government – a promise to lower taxes – can end up being a very complicated policy action, resulting in shifting tax burdens, complex tax codes, and regressive taxation schemes.

Put very simply, the BC Carbon Tax adds a tax of $30 for each tonne of C02 emitted. This is collected at the source – those businesses who are vendors of fossil fuels – and those costs will get passed on to whomever is buying the fuel. But it’s not just about rising fuel costs. The next three examples show how the Carbon Tax is currently working in BC, for better or for worse, and serve to illustrate the possible benefits of “tax”, something often considered a dirty word.

LJ’s Pizza

Laura Jane is a young entrepreneur who owns and runs LJ’s Brick-Oven Pizza and deliveries make up a significant part of her business. With the carbon tax, Laura will be forced to pay higher prices for gasoline. This doesn’t sit well with Laura. LJ’s Pizza has very small profit margins; with staff to pay and rising costs for ingredients, a small increase in gas prices means a significant reduction in profits. Laura gets upset, blames the government for gouging her with taxes, reads an op-ed in the local newspaper that suggests the carbon tax is hurting the economy, and votes accordingly.

Jenny’s Farm

Jenny considers herself an environmentalist. After settling down in the interior a number of years back, she and her family have had quite a lot of success growing and selling organic produce. Jenny tries her best to be energy efficient and use environmentally friendly products. What Jenny has no control over however is shipping costs. Jenny pays for a private trucking firm to pick up her produce and deliver it to market a few times per week. Faced with increasing fuel costs due to the carbon tax, the trucking company inevitably has to raise its rates, and this gets passed on to Jenny’s Farm. Although she doesn’t like it, Jenny understands that paying this little bit extra is the price she has to pay for her province to go green. She doesn’t really understand what happens to that money, but she has faith in her government.

Gord’s Trucking

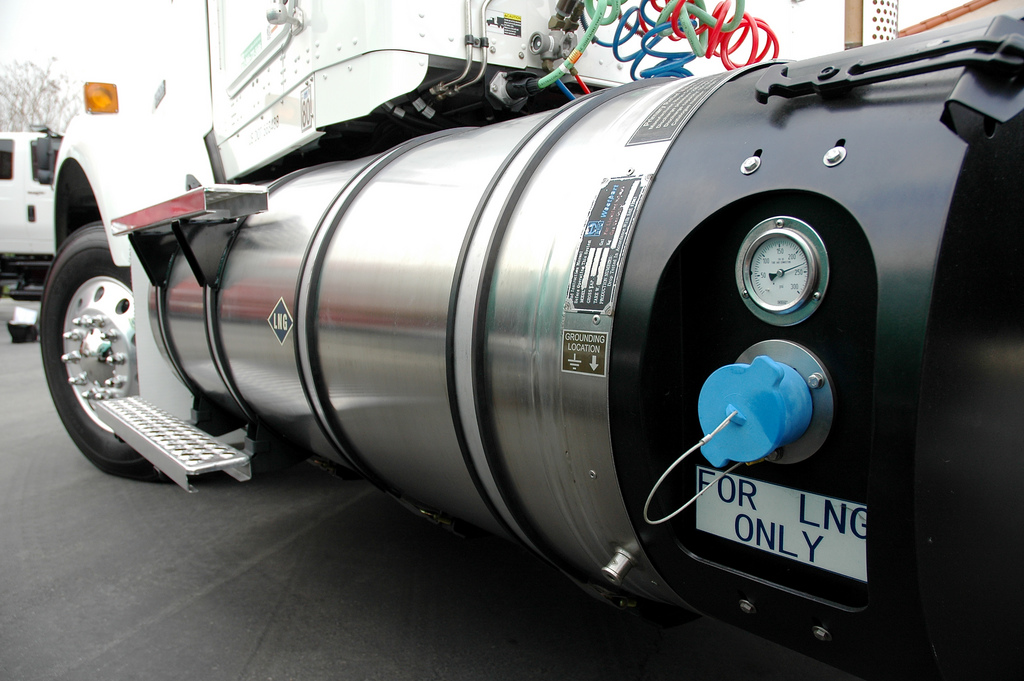

Gordon has been operating a trucking business in the lower mainland for over thirty years. He knows the ins and outs of the industry and runs a tight ship. He keeps his nose buried in newspapers, market reports, and the goings-on of the provincial government. When Gord hears that the BC Carbon Tax will increase his fuel costs substantially, he heads to his financial advisor. With the right advice, Gord makes a plan to retrofit his fleet to run on liquid natural gas (LNG), resulting in an estimated annual tax savings of $300,000. At a retrofit cost of $10,000 per truck, Gord realizes he can quickly turn those savings into profits.

Each of these three scenarios, and countless other variations, are playing out in BC right now. What could LJ do differently? She could start by changing her delivery schedule and routing to be more efficient, perhaps through a small investment in GPS technology. She could also stop using automobiles for delivery, and instead invest in a small fleet of LJ’s Pizza scooters. How about Jenny? Perhaps she could look for more affordable shipping options, like starting a shipping co-op with other farmers in the area. Gord has clearly done well for himself, and can either pocket the profits, or invest in even more efficient equipment, leading to additional savings.

Now what if all these three actors worked together? Jenny decides to switch to Gord’s Trucking in order to take advantage of his recently reduced rates, and be able to market her produce as being shipped by LNG. Thanks to these savings, Jenny is able to expand her business and starts focusing on new customers. She gets in touch with LJ, and becomes the main supplier of LJ’s Brick-Oven Pizza. LJ is now able to advertise local, organic produce, enabling her to slightly raise her prices; she now has room in her budget to buy that fleet of scooters. Her gasoline bills plummet, and that cash gets funnelled back into her business.

This very simplistic example just shows how a carbon tax can encourage efficiencies and eventually contribute to economic growth; it has also deliberately ignored the fact that a carbon tax has helped to keep income taxes and corporate income taxes to national lows. LJ, Jenny, and Gord’s employees will all be paying less in taxes – which means more money to spend on delicious brick-oven pizza.

This revenue-neutral tax is a model for other jurisdictions around the world. While the three-letter T word conjures up nightmares for most of us, we must step back from such reactions and see the tax for what it is: a way of decreasing our impact on the environment, while encouraging innovation and efficiencies, and overall tax savings to every resident of British Columbia.

(Feature photo courtesy of Stephen Petit/Flickr, pizza photo courtesy of Basheer Tome/Flickr)