“Vice cannot become virtue due to goodness of intention”

A word like fatwa can carry a lot of weight these days. It rings in the ear like jihad to the uninformed, and likely conjures up images of holy war, suicide bombings, beheading, and the complete irrationality of a fringe (but terrifying) extremist form of Islam. A non-Muslim however wouldn’t have any such visceral or knee-jerk reaction to a church decree, or a Supreme Court ruling. But essentially that’s what it is, or at least, that’s what it should be.

A fatwa is more or less an interpretive document of Islamic law and scripture, and very rarely deals with any kind of declaration of holy war or incitement to violence (Osama Bin Laden is a particularly unfortunate exception). However the fact of its relatively non-violent usage in history by no means makes a fatwa, as a concept and an institution, impervious to criticism. They range from the misinformed, to the blatantly political, to the bizarre: fatwa that forbid the vaccination of children, based on the assertion that they are a conspiracy by the “Jews”; fatwa against the smoking of cigarettes; fatwa calling for boycotts on products produced in the USA. The relevance and influence of a fatwa is of course determined by the scholar who issues it. And therein lies the danger, and the promise.

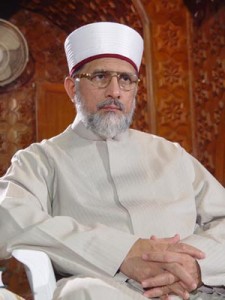

The man in the photo shown here is Tahir ul-Qadri, a prominent Islamic scholar from Pakistan. His recent fatwa, entitled “Fatwa on Suicide Bombings and Terrorism” has gained little to no attention in the western media. In the Islamic world however, it’s gained him a potential death sentence. According to Foreign Policy magazine, the Pakistani militant group Tehrik-e-Taliban has added Qadri’s name to their ‘death list’, all for his efforts at promoting peace and non-violence. While Qadri has not been the first to issue fatwa on this issue, the length, depth, and breadth of his work (and the readable English translation) make it important and worthy of attention.

The following quote is taken from the translated English introduction:

It may be true that among the fundamental local, national and international factors underpinning terrorism on a global level include: the injustices being currently meted out to the Muslims in certain matters, the apparent double standards displayed by the mainpowers, and their open-ended and long-term military engagements in a number of countries under the pretext of eliminating terror. But the terrorists’ recourse to violent and indiscriminate killings have become a routine affair, taking the form of suicide bombings against innocent and peaceful people, bomb blasts on mosques, shrines, educational institutions, bazaars, governmental buildings, trade centres, markets, security installations, and other public places: heinous, anti-human and barbarous acts in their very essence. These people justify their actions of human destruction and mass killing of innocent people in the name of Jihad (holy struggle against evil) and thus distort, twist and confuse the entire Islamic concept of Jihad.

These aren’t ground-breaking concepts. Qadri isn’t the first scholar, and hopefully won’t be the last, to preach the peaceful nature of Islam and underscore the perversion of the concept of jihad. The number of times President Obama has gone out of his way to label Islam as a religion of peace is beyond count, and he is not alone. But the young, angry, disenfranchised Muslims of an unstable Pakistan are unlikely to heed the words of an American president. The message gains its strength through the speaker, and when the Qur’an is quoted directly the message is even that much more striking:

“And among people there is also someone whose conversation seems to you pleasing in the life of the world and who calls Allāh to witness that which is in his heart, but in truth he is most quarrelsome. And when he turns away (from you), he runs about in the land to do (everything possible) to rouse mischief and destroy crops and life. And Allāh does not like mischief and violence. And when it is said to him (on account of this tyranny and violence): ‘Fear Allāh,’ his arrogance stimulates him for more sins. Hell is, therefore, sufficient for him. And that is indeed an evil abode.”(Al-Qur’an, 2:204-206)

Positive messages aside, to the casual western reader, it should be noted that the text is not without its issues. For instance, a passage advocating the responsibility of an Islamic state to firmly quash rebellion with an iron first can certainly be seen as justification for authoritarianism, whether the rebellion be “terrorist” or not. One need only recall the bloody response to the recent post-election demonstrations in Iran to see how this type of teaching can be seriously twisted. In any document of length (the original fatwa in Urdu reaches 600 pages) there will be plenty of opportunity for selectivity.

And therein lies the heart of the issue. For an atheist such as myself, religion is not created by divine word, but rather it is an amalgamation of scores of texts written by innumerable influential and biased individuals over thousands of years. That these words lack internal consistency is not surprising, and there is no doubt that any group or movement can seek and find justification for violent actions, or otherwise, by their own selective interpretation. Handing over reams of contradictory spiritual texts to an angry young man, but with the nasty bits highlighted, can sway such an influential mind searching for purpose.

What Qadri has done is present a thoroughly researched and undeniably Islamic text that has the seriously potential effect of affecting young minds towards peace. Or, barring that, at least away from senseless violence. It is just one more text among many, but one more that in its own small way brings balance to the argument. If conventionally western moral arguments (largely based on Christianity) do not influence extremist groups to change tactics, then perhaps this will. Regardless of your opinion on religion, or Islam in particular, the value in such an exercise is clear.

(Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, feature photo courtesy of manalahmadkhan/Flickr)