(This piece originally appeared on the Carbon Talks blog)

Except for a brief but quickly scuttled attempt in the early 1950s, taxation on tobacco products didn’t really take off in Canada until 1981. Rates rose dramatically until 1992, with the Canadian government increasing taxes on tobacco by 500%, subsequently leading to a significant decline in consumption of cigarettes. These taxes have been one of the highest profile Pigovian taxes – that is, a tax that is designed to discourage activities that generate negative externalities. In tandem with bans on advertising, warning labels, and other widespread campaigns, taxes on tobacco have caused consumption in Canada to plummet, decreasing from some 40% of the population in 1981, to just over 15% today.

This didn’t happen without opposition. A strong tobacco lobby fought for years to keep taxes low, arguments were made that such taxes were regressive and unfairly targeted lower income families, and increased smuggling due to market imbalances forced the government to rethink the entire system in the mid 1990’s. For anyone who has followed the discussion on the carbon tax in Canada, this will all start to sound familiar.

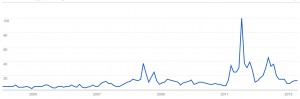

Though we’ve been talking about tobacco taxation for decades, it was only in 2008 that “carbon tax” became a commonly heard phrase in Canada. The introduction of the BC carbon tax in February 2008, followed by the Liberal Party of Canada campaigning on their “Green Shift” plan, meant that Canada was getting its first taste of something that Europe had been talking about for years: a sensible, modest, revenue-neutral price on carbon emissions. While the BC plan has since shown itself to be successful, at least in its currently frozen form, the “Green Shift” spelled doom for the Liberal Party of Canada, and carbon pricing has become a tool for political division rather than the basis of a discussion on progressive environmental policy.

So it came as a surprise last week when the Alberta government announced a proposed expansion of their own carbon pricing scheme. The proposal, dubbed 40/40, would charge a levy of $40 per tonne for up to 40% of a company’s emissions. This proposal has been welcomed by most in the environmental sector, but many have argued that it still does not go far enough. When compared to BC’s carbon tax, for example, it remains relatively weak: companies in Alberta will actually be paying $16 per tonne (40% of $40), almost half of the $30 currently in place in BC. All of these prices are easily within the range of the shadow price per tonne that almost all oil companies operating in Canada use to determine if a project makes economic sense. In other words, this proposal is very unlikely to shock the industry.

It is no coincidence that this proposal was released the week before Alberta Premier Alison Redford traveled to Washington to lobby for approval of the Keystone XL pipeline. The relative weakness of the proposal (despite it being much stronger than what anyone expected), combined with carefully chosen wording by Energy Minister Ken Hughes: “we have to earn the social license and the respect of other Canadians,” suggests that the proposal isn’t so much about emissions as it is about social and political capital. In fact the 40/40 proposal may not even see the light of day, as Premier Redford said “I wouldn’t characterize anything as a plan.” If this is simply an exercise in public relations in order to increase the chances of building an additional pipeline, then it doesn’t really get us much closer to the goal of reducing emissions; if Canada is to meet its climate goals by 2020, it’s estimated that a carbon price of $100 per tonne is necessary. So what is the goal? Emissions reductions, economic stimulus, social capital, public relations, or some combination thereof?

Until we are all speaking the same language, and working toward a common goal, then we remain on the lower rungs of a very tall ladder. At the bottom is the status quo. At the top is a national price on carbon strong enough to effect significant emissions reductions, wrapped in a mechanism that is predictable, effective, and understood. Alberta’s proposal, while welcome for its potential, is just one small step up, with many steps to go.

Until other jurisdictions catch up, it is unlikely that Alberta, BC, or any other province or state in the region will be able to implement a truly effective carbon tax. We may then find ourselves in a situation that affected tobacco taxes in 1994; with increased smuggling, the Canadian government decreased taxation in an effort to reduce illegal imports. Although those taxes eventually returned and surpassed 1993 levels, it has been a long process. Implementing a price on carbon will be a similarly long process, but there’s one vast difference between GHG emissions and the dangers of cigarettes: when it comes to climate, we’re all in this together.

(Icon photo courtesy of PremierofAlberta/Flickr, graph courtesy of Google trends)